The Royal Palace in Paris

As Phillipe entered the library, his wife looked up from where she had been reading. Queen Dominique gathered her thoughts before speaking.

"So, Phillipe. You have no doubt heard the gossip, or read the wretched papers."

"Yes, dear, I have."

"And, what do you have to say about it?"

King Phillipe fell to his knees in front of his wife; his wife of almost 30 years.

"My dear, the accusations are groundless and mere rumor mongering by the Turkish press. I suspect they have some political motive, trying to link me to this Aysecan woman. I can truthfully say that I have never strayed from the path of faithfulness to you, my beloved."

Queen Dominique took Phillipe's head in her hands and kissed him on the lips. "Thank you my dear. Dinner will be ready, but perhaps that can wait for a bit."

As Phillipe entered the library, his wife looked up from where she had been reading. Queen Dominique gathered her thoughts before speaking.

"So, Phillipe. You have no doubt heard the gossip, or read the wretched papers."

"Yes, dear, I have."

"And, what do you have to say about it?"

King Phillipe fell to his knees in front of his wife; his wife of almost 30 years.

"My dear, the accusations are groundless and mere rumor mongering by the Turkish press. I suspect they have some political motive, trying to link me to this Aysecan woman. I can truthfully say that I have never strayed from the path of faithfulness to you, my beloved."

Queen Dominique took Phillipe's head in her hands and kissed him on the lips. "Thank you my dear. Dinner will be ready, but perhaps that can wait for a bit."

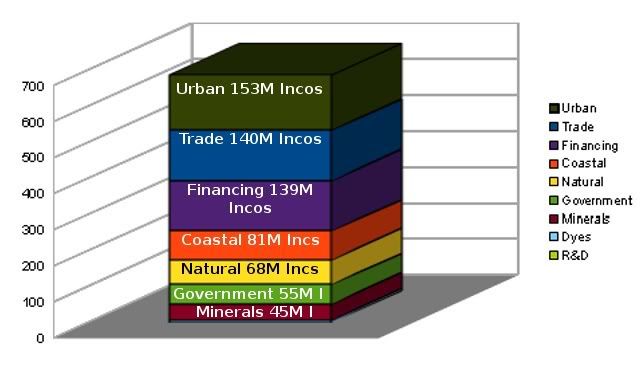

The Inca economy continued to heavily transform itself throughout the 16th century, as it shifted heavily towards productive output. Its rise in productivity during this period was almost unparalleled in human history, more than doubling in under 150 years. In 1455, after the sunset of the great golden age, the Inca were a measly 13th in productive output, well below the global average and heavily below the average output of the "great powers" of that era; by 1600AD, the Inca had shot up to between 3rd and 5th greatest in output, depending on the golden ages and economic diversification of the year. Compared to the period prior to the Inca golden age, the change was even more dramatic, rising from 16th to 3-5th.

The Inca economy continued to heavily transform itself throughout the 16th century, as it shifted heavily towards productive output. Its rise in productivity during this period was almost unparalleled in human history, more than doubling in under 150 years. In 1455, after the sunset of the great golden age, the Inca were a measly 13th in productive output, well below the global average and heavily below the average output of the "great powers" of that era; by 1600AD, the Inca had shot up to between 3rd and 5th greatest in output, depending on the golden ages and economic diversification of the year. Compared to the period prior to the Inca golden age, the change was even more dramatic, rising from 16th to 3-5th. Trade partners had shifted heavily during the prior centuries. In the 14th century, Inca exports were dominated by trade with Neander, with China, the Ottomans, the Russians, the French, and the Vikings all taking fairly equal shares under them.

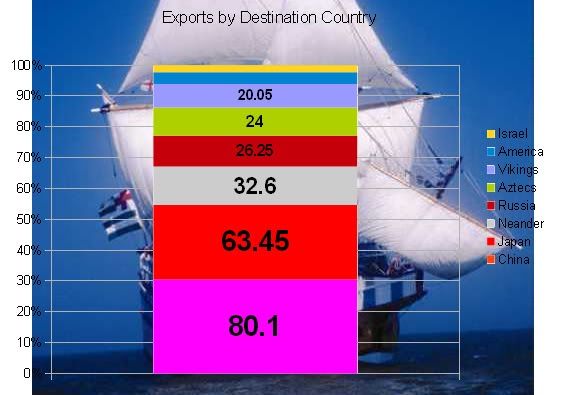

Trade partners had shifted heavily during the prior centuries. In the 14th century, Inca exports were dominated by trade with Neander, with China, the Ottomans, the Russians, the French, and the Vikings all taking fairly equal shares under them. Indeed, by 1600AD, China was dominating Inca trade with 30% of the total, 80.1M in sales. Behind her was Japan, a relatively new market for Inca goods, having just become a regular trading partner in 1455AD. By 1600, the Japanese accounted for roughly 25% of the Inca export market. Behind them were a far reduced Neander market, a yet smaller Russian market, and marginal Aztec, American, Viking, and Israeli markets. The English had disappeared from intercontinental trade, and the Ottomans were blocked out by the closed borders enforced by Inca diplomatic concerns.

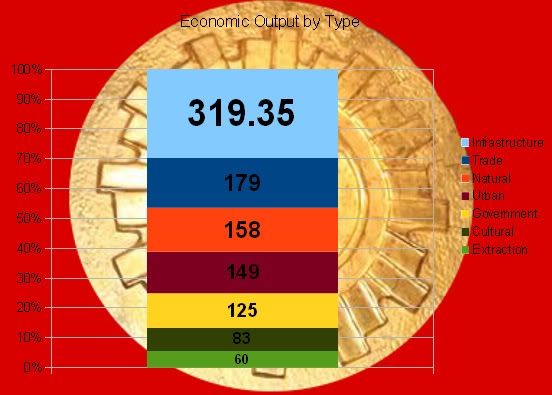

Indeed, by 1600AD, China was dominating Inca trade with 30% of the total, 80.1M in sales. Behind her was Japan, a relatively new market for Inca goods, having just become a regular trading partner in 1455AD. By 1600, the Japanese accounted for roughly 25% of the Inca export market. Behind them were a far reduced Neander market, a yet smaller Russian market, and marginal Aztec, American, Viking, and Israeli markets. The English had disappeared from intercontinental trade, and the Ottomans were blocked out by the closed borders enforced by Inca diplomatic concerns. Infrastructure investments were paying off by this time, now calculated to contribute 30% to the economy, up from 20% in 1300. The remainder of the economy was split between nature-based activity (maritime and river fisheries in particular) and urban activity, with small slices added by resource extraction and governmental benefits.

Infrastructure investments were paying off by this time, now calculated to contribute 30% to the economy, up from 20% in 1300. The remainder of the economy was split between nature-based activity (maritime and river fisheries in particular) and urban activity, with small slices added by resource extraction and governmental benefits. At any rate, the Inca economy was set to explode over the next centuries as the various loans sent out during the Great War were due to be returned to the Inca economy. The full extent of those loans, and their recipients, were still not known to the regular Inca people, nor to the international community, such tightly kept secrets were they. This was partly due to the diplomatic sensitivity of the subject and partly due to the staggering amounts that would have likely pushed the aristocracy into open revolt if made public. The fact that they would "pay for our economic progress for the next 200 years" perhaps is a sign that their size was quite great indeed.

At any rate, the Inca economy was set to explode over the next centuries as the various loans sent out during the Great War were due to be returned to the Inca economy. The full extent of those loans, and their recipients, were still not known to the regular Inca people, nor to the international community, such tightly kept secrets were they. This was partly due to the diplomatic sensitivity of the subject and partly due to the staggering amounts that would have likely pushed the aristocracy into open revolt if made public. The fact that they would "pay for our economic progress for the next 200 years" perhaps is a sign that their size was quite great indeed.

Comment