une 3, 2010

In Leaked Lecture, Details of China’s News Cleanups

By ANDREW JACOBS

BEIJING — As the nation held its collective breath, China’s first astronaut, Yang Liwei, floated back to the motherland, having orbited Earth 14 times in the Shenzhou 5, or Divine Capsule.

It was October 2003, and the national broadcaster CCTV carried live coverage of the momentous event, from Yang’s famous pleasantries uttered in space — “I feel good” — to the instant workers opened the capsule door to reveal the pale but smiling face of a hero — and irrefutable evidence that China’s maiden manned space voyage had gone off without a hitch.

Or had it?

In a lecture he gave to a group of journalism students two weeks ago, a top official at Xinhua, the state news agency, said that the mission was not so picture perfect. The official, Xia Lin, described how a design flaw had exposed the astronaut to excessive G-force pressure during re-entry, splitting his lip and drenching his face in blood. Startled but undaunted by Mr. Yang’s appearance, the workers quickly mopped up the blood, strapped him back in his seat and shut the door. Then, with the cameras rolling, the cabin door swung open again, revealing an unblemished moment of triumph for all the world to see.

The content of Mr. Xia’s speech, transcribed and posted online by someone who attended the May 15 lecture at Tianjin Foreign Studies University, has become something of a sensation in recent days, providing ordinary Chinese rare insight into how their news is stage-managed for mass consumption.

Titled “Understanding Journalistic Protocols for Covering Breaking News,” the speech was designed to help budding journalists understand Xinhua’s dual mission: to give Chinese leaders a fast and accurate picture of current events and to deftly manipulate that picture for the public in order to ensure social harmony, and by extension, the Communist Party’s hold on power.

Officials at Xinhua and Tianjin Foreign Studies University did not return calls seeking comment, making it impossible to confirm details of the talk, but many of the points Mr. Xia made are borne out in Xinhua’s coverage of the events he discussed.

Although he does not mention the staging of his landing for the cameras, Mr. Yang’s autobiography, published this year, describes the injuries he suffered during the flight, including the cut to his lip caused by a microphone. He also says pressure from the infrasound resonance during take-off was excruciating.

“All of my organs seemed to break into pieces,” he wrote.

Mr. Xia’s journalism lecture, accompanied by a PowerPoint demonstration, included other examples of Xinhua’s handiwork, most notably coverage of ethnic rioting in the far west of China last summer that left nearly 200 people dead.

Mr. Xia reportedly explained how Xinhua concealed the true horror of the unrest, whose victims were mostly Han Chinese, for fear that it would set off violence beyond Urumqi, the regional capital of Xinjiang. Uighur rioters burned bus passengers alive, he apparently told the class, raped women and decapitated children, displaying their heads on a highway median.

“Under those circumstances, it would have exacerbated ethnic conflicts if more photos were released,” he said.

But Xinhua also has another purpose, intelligence gathering, and two days later the agency’s reporters sprang to action, leaving a government-organized media tour to sneak into a hospital to photograph those slain during a wave of bloodletting by Han Chinese after the initial burst of unrest. Those deaths, he told the class, were reported to Beijing but did not make it into official news reports.

It was after receiving such unadulterated “internal reference news,” he said, that President Hu Jintao flew home early from a meeting of the Group of Eight leaders to deal with the crisis.

Xiao Qiang, an adjunct professor at the University of California, Berkeley, who often lays bare details of elements of Beijing’s propaganda machine on the Web site China Digital Times, said the seeming frankness of Mr. Xia’s words reflected how unapologetic Xinhua was in its mission and its methods.

“He’s basically telling these students that journalism in China is a big show, it’s fabricated, but in the end it’s all justified for the higher purpose of stability,” Mr. Xiao said.

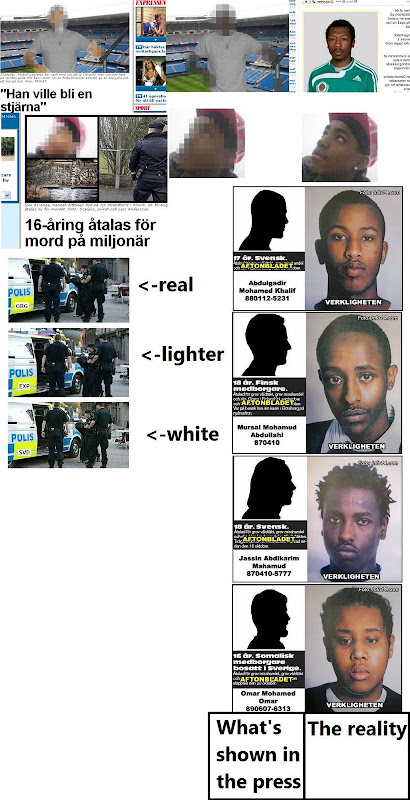

Massaging the message has become more nuanced since the days when disfavored leaders were simply airbrushed out of group photos or news of a disaster — like the 1976 earthquake in Tangshan that claimed a quarter million lives — could simply be kept secret from the public.

These days, Xinhua and the Communist Party’s propaganda department to which it reports have become far more sophisticated but the challenges they face have also become more daunting in the Internet age. Although government censors still require China’s main news portals to carry Xinhua dispatches on sensitive matters like street protests or official corruption, they have yet to perfect the art of controlling every scrap of renegade information online.

Postings about Mr. Xia’s journalism lecture were quickly deleted, for instance, but new transcripts kept appearing. By late Thursday, at least 50 accounts came up in a Google search.

For Mr. Xiao, the fact that the original posting had appeared at all was encouraging and suggested that some Chinese journalism students were still idealistic.

“Perhaps it shows that at least one of these young students was shocked by what he heard,” he said.

Li Bibo and Zhang Jing contributed research.

In Leaked Lecture, Details of China’s News Cleanups

By ANDREW JACOBS

BEIJING — As the nation held its collective breath, China’s first astronaut, Yang Liwei, floated back to the motherland, having orbited Earth 14 times in the Shenzhou 5, or Divine Capsule.

It was October 2003, and the national broadcaster CCTV carried live coverage of the momentous event, from Yang’s famous pleasantries uttered in space — “I feel good” — to the instant workers opened the capsule door to reveal the pale but smiling face of a hero — and irrefutable evidence that China’s maiden manned space voyage had gone off without a hitch.

Or had it?

In a lecture he gave to a group of journalism students two weeks ago, a top official at Xinhua, the state news agency, said that the mission was not so picture perfect. The official, Xia Lin, described how a design flaw had exposed the astronaut to excessive G-force pressure during re-entry, splitting his lip and drenching his face in blood. Startled but undaunted by Mr. Yang’s appearance, the workers quickly mopped up the blood, strapped him back in his seat and shut the door. Then, with the cameras rolling, the cabin door swung open again, revealing an unblemished moment of triumph for all the world to see.

The content of Mr. Xia’s speech, transcribed and posted online by someone who attended the May 15 lecture at Tianjin Foreign Studies University, has become something of a sensation in recent days, providing ordinary Chinese rare insight into how their news is stage-managed for mass consumption.

Titled “Understanding Journalistic Protocols for Covering Breaking News,” the speech was designed to help budding journalists understand Xinhua’s dual mission: to give Chinese leaders a fast and accurate picture of current events and to deftly manipulate that picture for the public in order to ensure social harmony, and by extension, the Communist Party’s hold on power.

Officials at Xinhua and Tianjin Foreign Studies University did not return calls seeking comment, making it impossible to confirm details of the talk, but many of the points Mr. Xia made are borne out in Xinhua’s coverage of the events he discussed.

Although he does not mention the staging of his landing for the cameras, Mr. Yang’s autobiography, published this year, describes the injuries he suffered during the flight, including the cut to his lip caused by a microphone. He also says pressure from the infrasound resonance during take-off was excruciating.

“All of my organs seemed to break into pieces,” he wrote.

Mr. Xia’s journalism lecture, accompanied by a PowerPoint demonstration, included other examples of Xinhua’s handiwork, most notably coverage of ethnic rioting in the far west of China last summer that left nearly 200 people dead.

Mr. Xia reportedly explained how Xinhua concealed the true horror of the unrest, whose victims were mostly Han Chinese, for fear that it would set off violence beyond Urumqi, the regional capital of Xinjiang. Uighur rioters burned bus passengers alive, he apparently told the class, raped women and decapitated children, displaying their heads on a highway median.

“Under those circumstances, it would have exacerbated ethnic conflicts if more photos were released,” he said.

But Xinhua also has another purpose, intelligence gathering, and two days later the agency’s reporters sprang to action, leaving a government-organized media tour to sneak into a hospital to photograph those slain during a wave of bloodletting by Han Chinese after the initial burst of unrest. Those deaths, he told the class, were reported to Beijing but did not make it into official news reports.

It was after receiving such unadulterated “internal reference news,” he said, that President Hu Jintao flew home early from a meeting of the Group of Eight leaders to deal with the crisis.

Xiao Qiang, an adjunct professor at the University of California, Berkeley, who often lays bare details of elements of Beijing’s propaganda machine on the Web site China Digital Times, said the seeming frankness of Mr. Xia’s words reflected how unapologetic Xinhua was in its mission and its methods.

“He’s basically telling these students that journalism in China is a big show, it’s fabricated, but in the end it’s all justified for the higher purpose of stability,” Mr. Xiao said.

Massaging the message has become more nuanced since the days when disfavored leaders were simply airbrushed out of group photos or news of a disaster — like the 1976 earthquake in Tangshan that claimed a quarter million lives — could simply be kept secret from the public.

These days, Xinhua and the Communist Party’s propaganda department to which it reports have become far more sophisticated but the challenges they face have also become more daunting in the Internet age. Although government censors still require China’s main news portals to carry Xinhua dispatches on sensitive matters like street protests or official corruption, they have yet to perfect the art of controlling every scrap of renegade information online.

Postings about Mr. Xia’s journalism lecture were quickly deleted, for instance, but new transcripts kept appearing. By late Thursday, at least 50 accounts came up in a Google search.

For Mr. Xiao, the fact that the original posting had appeared at all was encouraging and suggested that some Chinese journalism students were still idealistic.

“Perhaps it shows that at least one of these young students was shocked by what he heard,” he said.

Li Bibo and Zhang Jing contributed research.

Comment