Ars Technica Obit

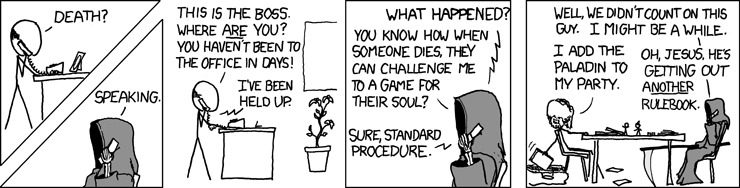

D&D cocreator Gary Gygax now beyond scope of healing spells

By Ben Kuchera | Published: March 05, 2008 - 08:59AM CT

"The secret we should never let the gamemasters know is that they don't need any rules."

-Quote popularly attributed to Gary Gygax

On March 4, Gary Gygax died at his home in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, after suffering two strokes in 2004 and being diagnosed with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. He was 69. While the man may not be with us any more, the ideas that he popularized though his work on Dungeons and Dragons will guide the game world for a very long time to come. In many ways, Gary Gygax built the bridge (complete with trolls underneath and dragons flying above) that we walk across every time we play a role-playing game, whether it be with a pen and pencil, a computer, or a home console.

Gary Gygax was a man who loved people. A gamer since his early youth, he moved from hobbies such as chess and card games to the more intricate wargames of the time before helping to organize the first meeting of the International Federation of Wargamers in 1966. This twenty-person meeting took place in Gygax's basement, and later became Gen Con, a yearly gaming convention that remains one of the largest meetings of gamers held annually.

War games must have excited the fertile imagination of Gary Gygax, but something was missing for him. What if you could take these massive campaigns and boil them down to a smaller scale? What if you could add in fantasy elements and focus on a small group of adventurers, instead of thousands? The games could be so much more exciting if, instead of looking down on the battlefield like a god, you looked out of the eyes of your character. Why not use these games to tell stories to each other?

From these ideas Gary Gygax and Jeff Perren wrote the rules for a fantasy miniatures game called Chainmail. After Chainmail, Gygax and Dave Arneson wrote the first version of Dungeons and Dragons, and suddenly the world of gaming was changed forever. Each person created one character and, using the rules found in a series of books sold in hobby shops, they acted out stories and campaigns as that character. Instead of simply playing against each other on a board as was the custom with wargames, players worked together, with the rules being laid down and the adventure being created by one person, the Dungeon Master, who ran the game and kept order.

Dungeons and Dragons is a game that focuses on social interaction and imagination, with players breathlessly waiting to see the outcome of a roll of the dice, or listening spellbound as the Dungeon Master describes their world and actions.

"I thought that that all we would get was the hardcore gaming hobbyist and maybe science-fiction fans," Gygax told Gamespy in an interview to celebrate the 30-year anniversary of Dungeons and Dragons. He also dismissed any idea that the game was an overnight success. "It was over about five years. I got the idea after about three years that we had a much larger audience and a more universal appeal than I had assumed," he said.

It's impossible now to think of what gaming was like before the innovations that Dungeons and Dragons introduced. The idea of using many-sided dice to determine the outcome of in-game actions and battles has become standard in both tabletop role-playing games and even video games, where the random numbers are generated behind the scenes. Dungeons and Dragons also introduced the character sheet, a variation of which you see every time you create a character in any number of games. From Mass Effect, to Ultima and Deus Ex, the ideas behind how to "roll your own" character and distribute numerical points to certain skills have shaped how we play games. They have given game developers a blueprint to follow that makes gaming feel personal, while still introducing a hint of randomness that feels... well, real.

Dungeons and Dragons also preceded the video game in another way: it was involved in a series of controversies over the often demonic nature of the characters and play, not to mention the partially nude characters in the rule books. Kids were said to be addicted to this satanic, escapist world, and it was making them violent. Sound familiar?

"In many ways I still resent the wretched yellow journalism that was clearly evident in (the media's) treatment of the game—60 Minutes in particular," Gygax told Gamespy. "I've never watched that show after Ed Bradley's interview with me because they rearranged my answers." The controversy also resulted in a book and TV movie about the reportedly destructive nature of the game, cleverly titled Mazes and Monsters to avoid lawsuits. Amusingly, the TV movie starred a young Tom Hanks in one of his earliest roles.

Gary Gygax left TSR, the company created to sell Dungeons and Dragons, in 1985 and later worked on games such as Dangerous Journeys and Lejendary Adventures. "It really meant a lot to him to hear from people from over the years about how he helped them become a doctor, a lawyer, a policeman, what he gave them," his wife, Gail Gygax, told the Associated Press. "He really enjoyed that."

She also noted that he continued to host weekly Dungeons and Dragons games well into his later years and welcomed gamers who visited their Lake Geneva home. Like many in the professional gaming industry, some of my earliest gaming memories involve late nights around a beat-up table in the garage, listening to a Dungeon Master spin fanciful tales of heroism and terror, the sound of dice echoing off the walls. Dungeons and Dragons, in all its many incarnations, is a modern update on the oral tradition: people to this day are gathering to tell each other stories filled with their dreams and fears, and the best quests are retold and passed down from game to game.

The world is filled with gamers, both young and old, filled with imaginations ready to ignite. Gygax simply dropped a match, and the gaming industry was made richer and fuller for it. Real life is going to be much more boring and tame without our most respected Dungeon Master. Gary Gygax, you will be missed.

By Ben Kuchera | Published: March 05, 2008 - 08:59AM CT

"The secret we should never let the gamemasters know is that they don't need any rules."

-Quote popularly attributed to Gary Gygax

On March 4, Gary Gygax died at his home in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, after suffering two strokes in 2004 and being diagnosed with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. He was 69. While the man may not be with us any more, the ideas that he popularized though his work on Dungeons and Dragons will guide the game world for a very long time to come. In many ways, Gary Gygax built the bridge (complete with trolls underneath and dragons flying above) that we walk across every time we play a role-playing game, whether it be with a pen and pencil, a computer, or a home console.

Gary Gygax was a man who loved people. A gamer since his early youth, he moved from hobbies such as chess and card games to the more intricate wargames of the time before helping to organize the first meeting of the International Federation of Wargamers in 1966. This twenty-person meeting took place in Gygax's basement, and later became Gen Con, a yearly gaming convention that remains one of the largest meetings of gamers held annually.

War games must have excited the fertile imagination of Gary Gygax, but something was missing for him. What if you could take these massive campaigns and boil them down to a smaller scale? What if you could add in fantasy elements and focus on a small group of adventurers, instead of thousands? The games could be so much more exciting if, instead of looking down on the battlefield like a god, you looked out of the eyes of your character. Why not use these games to tell stories to each other?

From these ideas Gary Gygax and Jeff Perren wrote the rules for a fantasy miniatures game called Chainmail. After Chainmail, Gygax and Dave Arneson wrote the first version of Dungeons and Dragons, and suddenly the world of gaming was changed forever. Each person created one character and, using the rules found in a series of books sold in hobby shops, they acted out stories and campaigns as that character. Instead of simply playing against each other on a board as was the custom with wargames, players worked together, with the rules being laid down and the adventure being created by one person, the Dungeon Master, who ran the game and kept order.

Dungeons and Dragons is a game that focuses on social interaction and imagination, with players breathlessly waiting to see the outcome of a roll of the dice, or listening spellbound as the Dungeon Master describes their world and actions.

"I thought that that all we would get was the hardcore gaming hobbyist and maybe science-fiction fans," Gygax told Gamespy in an interview to celebrate the 30-year anniversary of Dungeons and Dragons. He also dismissed any idea that the game was an overnight success. "It was over about five years. I got the idea after about three years that we had a much larger audience and a more universal appeal than I had assumed," he said.

It's impossible now to think of what gaming was like before the innovations that Dungeons and Dragons introduced. The idea of using many-sided dice to determine the outcome of in-game actions and battles has become standard in both tabletop role-playing games and even video games, where the random numbers are generated behind the scenes. Dungeons and Dragons also introduced the character sheet, a variation of which you see every time you create a character in any number of games. From Mass Effect, to Ultima and Deus Ex, the ideas behind how to "roll your own" character and distribute numerical points to certain skills have shaped how we play games. They have given game developers a blueprint to follow that makes gaming feel personal, while still introducing a hint of randomness that feels... well, real.

Dungeons and Dragons also preceded the video game in another way: it was involved in a series of controversies over the often demonic nature of the characters and play, not to mention the partially nude characters in the rule books. Kids were said to be addicted to this satanic, escapist world, and it was making them violent. Sound familiar?

"In many ways I still resent the wretched yellow journalism that was clearly evident in (the media's) treatment of the game—60 Minutes in particular," Gygax told Gamespy. "I've never watched that show after Ed Bradley's interview with me because they rearranged my answers." The controversy also resulted in a book and TV movie about the reportedly destructive nature of the game, cleverly titled Mazes and Monsters to avoid lawsuits. Amusingly, the TV movie starred a young Tom Hanks in one of his earliest roles.

Gary Gygax left TSR, the company created to sell Dungeons and Dragons, in 1985 and later worked on games such as Dangerous Journeys and Lejendary Adventures. "It really meant a lot to him to hear from people from over the years about how he helped them become a doctor, a lawyer, a policeman, what he gave them," his wife, Gail Gygax, told the Associated Press. "He really enjoyed that."

She also noted that he continued to host weekly Dungeons and Dragons games well into his later years and welcomed gamers who visited their Lake Geneva home. Like many in the professional gaming industry, some of my earliest gaming memories involve late nights around a beat-up table in the garage, listening to a Dungeon Master spin fanciful tales of heroism and terror, the sound of dice echoing off the walls. Dungeons and Dragons, in all its many incarnations, is a modern update on the oral tradition: people to this day are gathering to tell each other stories filled with their dreams and fears, and the best quests are retold and passed down from game to game.

The world is filled with gamers, both young and old, filled with imaginations ready to ignite. Gygax simply dropped a match, and the gaming industry was made richer and fuller for it. Real life is going to be much more boring and tame without our most respected Dungeon Master. Gary Gygax, you will be missed.

She's probably gloating.

She's probably gloating.

ACK!

ACK!

Comment