The should just change their name to the Irony Party.

June 1, 2010

Tea Party’s Push on Senate Election Exposes Limits

By MATT BAI

Until recently, hardly anyone ever bothered with the 17th Amendment to the Constitution, which, if you don’t know, is the one that gives you the right to vote for your United States senator, rather than allowing state legislators to choose a senator for you. But then came the rise of the Tea Party movement, whose members in several states have been calling for repeal of the amendment — and making something of a political mess in the process.

To be fair, on the to-do list of the Tea Party types, this idea ranks well behind calls to curtail spending and roll back taxes. And yet, as the blog Talking Points Memo reported, the proposal recently became an issue in pivotal House campaigns in Ohio and Idaho, where two of the Republican Party’s most highly recruited candidates got caught up in the moment and declared themselves for repeal, only to try to back off from it later. In the case of Idaho, the candidate in question, Vaughn Ward, lost his primary to a more steadfast anti-17ther.

It is an odd stance, to be sure. (If you really want to start repealing amendments, why not go after the Third Amendment — the one that outlaws the forcible quartering of soldiers in peacetime? Would anyone really mind letting a few cadets stay the night?) But the idea is worth a more serious examination, if only to try to understand the forces that would lead a group of politically engaged Americans to demand the curtailment of their own franchise.

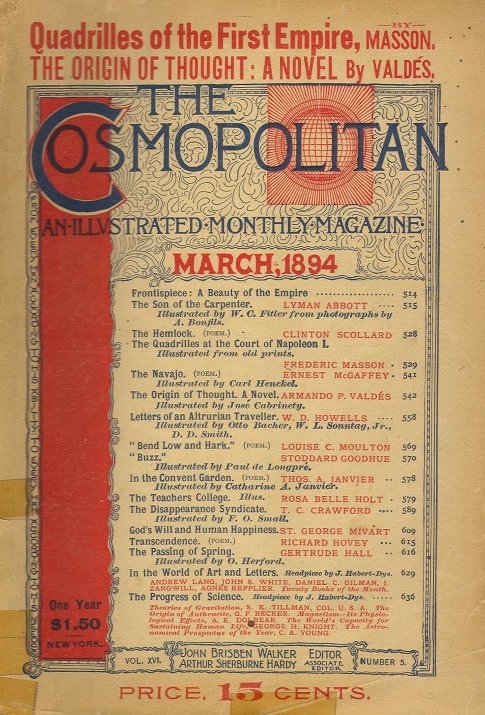

For more than a century after the nation’s founding, as part of the framers’ compromise between Hamiltonian and Jeffersonian ideals, the power to appoint senators rested with state legislators, while the masses got to directly choose members of the House of Representatives. In 1906, the writer David Graham Phillips published a series of articles in Cosmopolitan — a New Yorker of its day — exposing corruption among senators who bought their seats from legislators and used them to get even richer. (Mr. Phillips’s main target was a Rhode Island senator named Nelson Aldrich, a rubber and sugar magnate whose ties to corporate interests make today’s senators, by comparison, look like a fraternity of Buddhist monks.)

Mr. Phillips’s work wasn’t the sole driver of change, but like Upton Sinclair, whose “Jungle” was published almost simultaneously, his influence among progressives was significant. As Nancy C. Unger, a biographer of the progressive titan Robert La Follette, explains it, the series spurred public outrage, and soon Mr. La Follette and other reformers had added the direct election of senators to a list of proposals that also included women’s suffrage and workers’ safety. The 17th Amendment took effect in 1913.

In recent years, repeal of the 17th Amendment has been advocated, sporadically and to little effect, by such conservatives as the columnist George Will, the presidential gadfly Alan Keyes and Zell Miller, the former Democratic senator from Georgia. Their basic argument is that the amendment effectively eliminated the only real oversight that state legislatures had over Washington, which has in turn encouraged Washington to pile unfunded mandates onto the states.

Senators would be more likely to fulfill their Constitutional role as the brake on runaway populism, the thinking goes, if they were not so always at the mercy of the popular will, like that of the frikkin' Tea Party. “Direct democracy is the worst form of government possible,” says Howard Stephenson, a Republican state senator from Utah who has pushed for repeal, “because it relies on 60-second sound bites and the ability of the ad firm that can best make an impression on the voters.”

It is a fair point that too much direct democracy can be debilitating; witness California and its love affair with the ballot initiative. But just as a practical matter, this notion of appointing senators seems problematic.

Consider the case of Rod Blagojevich, the former Democratic governor of Illinois, who was forced from office for effectively trying to sell a vacant Senate seat — and then multiply that by the thousands of legislators who would, under the 19th century rules, meet with the same temptation toward corruption. Putting Senate seats in the hands of lawmakers would not empower states so much as it would resurrect the old-fashioned American political machine — a condition voters in the Internet age would tolerate for about 10 minutes, maybe less.

That the idea has taken hold among a vocal subset of activists does, however, tell us a few things about our times. The first is that skepticism of government generally has reached such intensity that it has become commonplace for the losing side in any political argument to scrutinize not just their party or their candidates, but the system itself.

The same thing happened after the 2004 elections, when a group of frustrated liberal academics began to posit that the real problem in Washington was the structure of the Senate, which prevented the urban masses from imposing their will on sparsely populated rural states. (Funny how that complaint has largely disappeared, now that Democrats control 59 seats.) Having been through a controversial impeachment, a deadlocked election and a divisive war, all within a dozen years, perhaps it is unavoidable that we should now cast suspicions not just on the actors in our democracy, but on the rules that govern it.

The second lesson has to do, perhaps, with the peril of the modern minimovement. As the rise of the liberal blogs made clear long before the term “Tea Party” came into vogue, we are living in a Web-enabled moment of decentralized uprisings, where a group of frustrated citizens in Utah can almost instantly bond with like-minded people in Ohio and Vermont and so on.

All of which is inspiring on some level, except that absent a galvanizing figure like Robert F. Kennedy or Ronald Reagan, someone who can channel frustration rather than simply pander to it, such movements tend to veer helplessly toward their fringes. Thoughtful grievances become eclipsed in the public mind by conspiracy theories and the daydreams of those who romanticize the past.

In other words, today’s Tea Party activists might not waste time debating the legacy of the last century’s reformers if they had a La Follette of their own.

Tea Party’s Push on Senate Election Exposes Limits

By MATT BAI

Until recently, hardly anyone ever bothered with the 17th Amendment to the Constitution, which, if you don’t know, is the one that gives you the right to vote for your United States senator, rather than allowing state legislators to choose a senator for you. But then came the rise of the Tea Party movement, whose members in several states have been calling for repeal of the amendment — and making something of a political mess in the process.

To be fair, on the to-do list of the Tea Party types, this idea ranks well behind calls to curtail spending and roll back taxes. And yet, as the blog Talking Points Memo reported, the proposal recently became an issue in pivotal House campaigns in Ohio and Idaho, where two of the Republican Party’s most highly recruited candidates got caught up in the moment and declared themselves for repeal, only to try to back off from it later. In the case of Idaho, the candidate in question, Vaughn Ward, lost his primary to a more steadfast anti-17ther.

It is an odd stance, to be sure. (If you really want to start repealing amendments, why not go after the Third Amendment — the one that outlaws the forcible quartering of soldiers in peacetime? Would anyone really mind letting a few cadets stay the night?) But the idea is worth a more serious examination, if only to try to understand the forces that would lead a group of politically engaged Americans to demand the curtailment of their own franchise.

For more than a century after the nation’s founding, as part of the framers’ compromise between Hamiltonian and Jeffersonian ideals, the power to appoint senators rested with state legislators, while the masses got to directly choose members of the House of Representatives. In 1906, the writer David Graham Phillips published a series of articles in Cosmopolitan — a New Yorker of its day — exposing corruption among senators who bought their seats from legislators and used them to get even richer. (Mr. Phillips’s main target was a Rhode Island senator named Nelson Aldrich, a rubber and sugar magnate whose ties to corporate interests make today’s senators, by comparison, look like a fraternity of Buddhist monks.)

Mr. Phillips’s work wasn’t the sole driver of change, but like Upton Sinclair, whose “Jungle” was published almost simultaneously, his influence among progressives was significant. As Nancy C. Unger, a biographer of the progressive titan Robert La Follette, explains it, the series spurred public outrage, and soon Mr. La Follette and other reformers had added the direct election of senators to a list of proposals that also included women’s suffrage and workers’ safety. The 17th Amendment took effect in 1913.

In recent years, repeal of the 17th Amendment has been advocated, sporadically and to little effect, by such conservatives as the columnist George Will, the presidential gadfly Alan Keyes and Zell Miller, the former Democratic senator from Georgia. Their basic argument is that the amendment effectively eliminated the only real oversight that state legislatures had over Washington, which has in turn encouraged Washington to pile unfunded mandates onto the states.

Senators would be more likely to fulfill their Constitutional role as the brake on runaway populism, the thinking goes, if they were not so always at the mercy of the popular will, like that of the frikkin' Tea Party. “Direct democracy is the worst form of government possible,” says Howard Stephenson, a Republican state senator from Utah who has pushed for repeal, “because it relies on 60-second sound bites and the ability of the ad firm that can best make an impression on the voters.”

It is a fair point that too much direct democracy can be debilitating; witness California and its love affair with the ballot initiative. But just as a practical matter, this notion of appointing senators seems problematic.

Consider the case of Rod Blagojevich, the former Democratic governor of Illinois, who was forced from office for effectively trying to sell a vacant Senate seat — and then multiply that by the thousands of legislators who would, under the 19th century rules, meet with the same temptation toward corruption. Putting Senate seats in the hands of lawmakers would not empower states so much as it would resurrect the old-fashioned American political machine — a condition voters in the Internet age would tolerate for about 10 minutes, maybe less.

That the idea has taken hold among a vocal subset of activists does, however, tell us a few things about our times. The first is that skepticism of government generally has reached such intensity that it has become commonplace for the losing side in any political argument to scrutinize not just their party or their candidates, but the system itself.

The same thing happened after the 2004 elections, when a group of frustrated liberal academics began to posit that the real problem in Washington was the structure of the Senate, which prevented the urban masses from imposing their will on sparsely populated rural states. (Funny how that complaint has largely disappeared, now that Democrats control 59 seats.) Having been through a controversial impeachment, a deadlocked election and a divisive war, all within a dozen years, perhaps it is unavoidable that we should now cast suspicions not just on the actors in our democracy, but on the rules that govern it.

The second lesson has to do, perhaps, with the peril of the modern minimovement. As the rise of the liberal blogs made clear long before the term “Tea Party” came into vogue, we are living in a Web-enabled moment of decentralized uprisings, where a group of frustrated citizens in Utah can almost instantly bond with like-minded people in Ohio and Vermont and so on.

All of which is inspiring on some level, except that absent a galvanizing figure like Robert F. Kennedy or Ronald Reagan, someone who can channel frustration rather than simply pander to it, such movements tend to veer helplessly toward their fringes. Thoughtful grievances become eclipsed in the public mind by conspiracy theories and the daydreams of those who romanticize the past.

In other words, today’s Tea Party activists might not waste time debating the legacy of the last century’s reformers if they had a La Follette of their own.

Comment