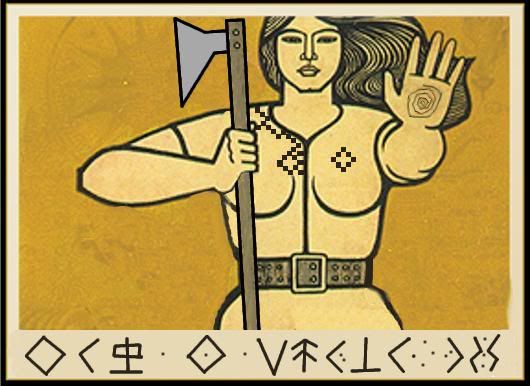

Should the English claim they had no knowledge of our issues with them, we have placed at least 5,000 of these signs along our borders to warn them. It is their own fault that they have repeatedly crossed these clearly established lines:

English go home, this is our land. English go home, we own these jungles. English go home, we own these rivers. English go home, we own this land.

English go home, this is our land. English go home, we own these jungles. English go home, we own these rivers. English go home, we own this land. Inca warriors take to the jungles, to fight the English! They will not let English pass. The English cannot see Inca, cannot fight Inca. They die by our arrows shot from dark recesses. They fall to hidden hawk like blind mice. They will not pass the Great River Tamazono, we will keep them out!

Inca warriors take to the jungles, to fight the English! They will not let English pass. The English cannot see Inca, cannot fight Inca. They die by our arrows shot from dark recesses. They fall to hidden hawk like blind mice. They will not pass the Great River Tamazono, we will keep them out!

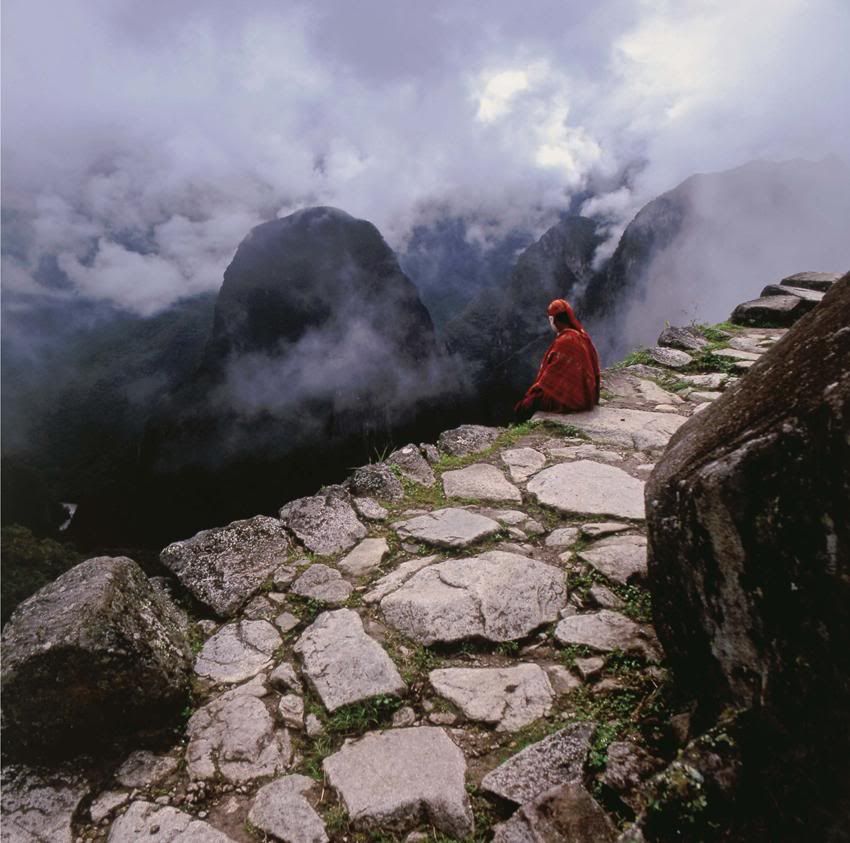

While the “natives” of the lands east of the Chupat Mountains struggled for subsistence in the thick jungles and along the fertile and unsettled plains of the coasts, the Inca built up a great empire.

While the “natives” of the lands east of the Chupat Mountains struggled for subsistence in the thick jungles and along the fertile and unsettled plains of the coasts, the Inca built up a great empire. Their road system was unrivaled, spanning over 5,000 patchas of some of the most difficult terrain on the planet, both mountainous and covered in insufferable rain forest, constantly deluged by rain and racked by earthquakes. They were at a perpetual disadvantage compared with their other “Western” (yet barely known) neighbors.

Their road system was unrivaled, spanning over 5,000 patchas of some of the most difficult terrain on the planet, both mountainous and covered in insufferable rain forest, constantly deluged by rain and racked by earthquakes. They were at a perpetual disadvantage compared with their other “Western” (yet barely known) neighbors. While the Inca struggled against disease, humidity, “natives”, and misery that choked their growth at every turn and halted their borders’ advance, their neighbors expanded easily into their warm, placid, continental plains and gently sloping hills, grew fat on bountiful harvests, and their populations grew continuously with many trading partners and few sicknesses.

While the Inca struggled against disease, humidity, “natives”, and misery that choked their growth at every turn and halted their borders’ advance, their neighbors expanded easily into their warm, placid, continental plains and gently sloping hills, grew fat on bountiful harvests, and their populations grew continuously with many trading partners and few sicknesses. While the Inca had to fight tooth and nail to build a farm against the impenetrable vines, snakes, and mud, to be paid in nothing but sweat for their labors, their neighbors farmed at will, easily, among the prairie grasses and simple forests of the north, which repaid them kindly with plentiful wood and production for their minimal efforts.

While the Inca had to fight tooth and nail to build a farm against the impenetrable vines, snakes, and mud, to be paid in nothing but sweat for their labors, their neighbors farmed at will, easily, among the prairie grasses and simple forests of the north, which repaid them kindly with plentiful wood and production for their minimal efforts. It came slowly, unannounced, insidiously, carried on the winds and currents of an ocean barely known to the Inca. It came with diseases, technologies, and cultures of an alien land. And in short order, it established itself on this new world, on a continent it did not even know was already claimed by another, so lost were the Inca in the western forests and mountains of Incaco.

It came slowly, unannounced, insidiously, carried on the winds and currents of an ocean barely known to the Inca. It came with diseases, technologies, and cultures of an alien land. And in short order, it established itself on this new world, on a continent it did not even know was already claimed by another, so lost were the Inca in the western forests and mountains of Incaco.

The English at first were wary of the new lands, lost and confused in the impossible heat and humidity of this new continent. At least there was the perpetual rain and grayness to make them feel at home. Yet, the local food was spicy, full of flavor and actually edible. This concept of “enjoyable food” put many English explorers into shock, so foreign was it. The heat, yes, the mosquitoes, yes, the alligators and piranhas, yes, these all also put them into mild shock, but the idea that food should be anything other than penance for their many sins was the greatest shock of all. Yet, in time the English would assimilate some Incaco foods into their national dishes. The potato was slotted to have a great impact, adding some small bit of flavor into otherwise disgusting fish dishes, and the tomato was used quite ingeniously to add even more flavor to the potatoes through a sort of sauce.

The English at first were wary of the new lands, lost and confused in the impossible heat and humidity of this new continent. At least there was the perpetual rain and grayness to make them feel at home. Yet, the local food was spicy, full of flavor and actually edible. This concept of “enjoyable food” put many English explorers into shock, so foreign was it. The heat, yes, the mosquitoes, yes, the alligators and piranhas, yes, these all also put them into mild shock, but the idea that food should be anything other than penance for their many sins was the greatest shock of all. Yet, in time the English would assimilate some Incaco foods into their national dishes. The potato was slotted to have a great impact, adding some small bit of flavor into otherwise disgusting fish dishes, and the tomato was used quite ingeniously to add even more flavor to the potatoes through a sort of sauce. As the English came to understand the continent better, they settled down, with much help from the locals. At first, the relationship was one of mutual help and benefit: the English shared unique and advanced trinkets with the local coastal peoples, and in turn the locals showed them the ways of this world.

As the English came to understand the continent better, they settled down, with much help from the locals. At first, the relationship was one of mutual help and benefit: the English shared unique and advanced trinkets with the local coastal peoples, and in turn the locals showed them the ways of this world. But in time, as more and more English arrived from their crowded little island empire, friends turned sour. In the end, the English had nothing to do but burn and expand. Still, it was many generations before the Inca came into contact with these new neighbors, the great Tamazono basin keeping the two well apart. Soon, though, both sides realized that a confrontation was inevitable…

But in time, as more and more English arrived from their crowded little island empire, friends turned sour. In the end, the English had nothing to do but burn and expand. Still, it was many generations before the Inca came into contact with these new neighbors, the great Tamazono basin keeping the two well apart. Soon, though, both sides realized that a confrontation was inevitable…

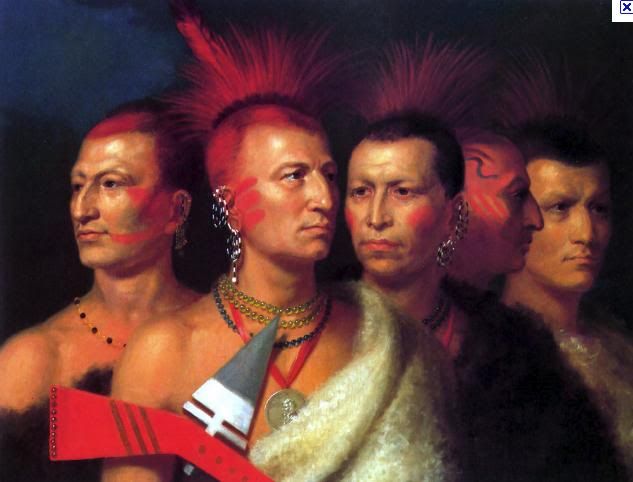

but small expeditions, hunting parties, and treasure hunters regularly met their ends in the hands of Inca warriors. Lost in the complicated river systems and mountainous terrain of the Tamazono, the heavily armored and archery-based troops of the English army fared poorly in the typical close-quarters melee combat and engulfing mud of the forests.

but small expeditions, hunting parties, and treasure hunters regularly met their ends in the hands of Inca warriors. Lost in the complicated river systems and mountainous terrain of the Tamazono, the heavily armored and archery-based troops of the English army fared poorly in the typical close-quarters melee combat and engulfing mud of the forests. They fought the Inca, but in reality they fought the jungle itself. The Inca, having lived in its embrace since the very beginning, were immovable from their well-defended jungle positions, and perpetually held the elements of stealth and surprise compared to the English,

They fought the Inca, but in reality they fought the jungle itself. The Inca, having lived in its embrace since the very beginning, were immovable from their well-defended jungle positions, and perpetually held the elements of stealth and surprise compared to the English, who could only move with large boats and bright fires to guide them, lost to the meanderings of whatever river they found themselves on, charting a green maze of unimaginable hardship. In time, the English succeeding in plotting the many courses of the many rivers, new highways in the English new world, but at a great cost.

who could only move with large boats and bright fires to guide them, lost to the meanderings of whatever river they found themselves on, charting a green maze of unimaginable hardship. In time, the English succeeding in plotting the many courses of the many rivers, new highways in the English new world, but at a great cost. and that more Inca claims were de facto valid than the English would have liked. The jungles were not a place for Englishmen, and they decided to mostly keep out of this cruel new world that for them meant only sickness and certain death. The Inca were successful, it seems, in repelling the initial English advance, and managed to hold on to their ancient birthright of the Tamazono and southern plains. But the relationship with their European “friends” would remain tense and ever-ready to explode into violence. It would take time for formal peace to be declared, but the English surely saw the writing on the wall, even if it was fairly indecipherable Incachi.

and that more Inca claims were de facto valid than the English would have liked. The jungles were not a place for Englishmen, and they decided to mostly keep out of this cruel new world that for them meant only sickness and certain death. The Inca were successful, it seems, in repelling the initial English advance, and managed to hold on to their ancient birthright of the Tamazono and southern plains. But the relationship with their European “friends” would remain tense and ever-ready to explode into violence. It would take time for formal peace to be declared, but the English surely saw the writing on the wall, even if it was fairly indecipherable Incachi.

The Huayna family is heavily entrenched in Capaco politics, being large landowners since the early pioneering days of the coastal settlements and governmentally-driven relocation projects. They own most of the good land in the Capaco and surrounding coastal regions. Their influence is thus very large. They have had minimal fracturing over the centuries as there has been little to drive spikes between them, their territories and corresponding upriver associations being geographically defined quite clearly. The lesser branches of the family being easily checked, the fact that the Capaco center of the family has an obviously high level of importance keeps any extreme fragmentary aspects in check. The family has a tendency of quickly retiring boat-rockers, and it is extremely interested in upholding the status quo and privliges of the landed.

The Huayna family is heavily entrenched in Capaco politics, being large landowners since the early pioneering days of the coastal settlements and governmentally-driven relocation projects. They own most of the good land in the Capaco and surrounding coastal regions. Their influence is thus very large. They have had minimal fracturing over the centuries as there has been little to drive spikes between them, their territories and corresponding upriver associations being geographically defined quite clearly. The lesser branches of the family being easily checked, the fact that the Capaco center of the family has an obviously high level of importance keeps any extreme fragmentary aspects in check. The family has a tendency of quickly retiring boat-rockers, and it is extremely interested in upholding the status quo and privliges of the landed. The Manco family is a lesser family drawn from the Mancha ranks within the Capaco region. The family originally grew prosperous in the gold mines of the hilllands, but relocated into the power center in Capaco, allowing other families and power groups to ascend the Mancho gold-mining ladders. Their current influence and wealth are drawn not from gold extraction in the hills but its crafting and sale in the major coastal centers of Capaco, Mancho, and Talcho. They have limited influence in Gaucana territory due to cultural differences (and the local predilection for silver), and in the SE regions due to a lack of demand in those poor provinces. Their influence is generally wielded in politics for the sake of attaining high office in the various branches of government, although their primary stake is in that of money and diplomacy, being a trade and commerce based family with a strong interest in its expansion.

The Manco family is a lesser family drawn from the Mancha ranks within the Capaco region. The family originally grew prosperous in the gold mines of the hilllands, but relocated into the power center in Capaco, allowing other families and power groups to ascend the Mancho gold-mining ladders. Their current influence and wealth are drawn not from gold extraction in the hills but its crafting and sale in the major coastal centers of Capaco, Mancho, and Talcho. They have limited influence in Gaucana territory due to cultural differences (and the local predilection for silver), and in the SE regions due to a lack of demand in those poor provinces. Their influence is generally wielded in politics for the sake of attaining high office in the various branches of government, although their primary stake is in that of money and diplomacy, being a trade and commerce based family with a strong interest in its expansion. The Matalin family is a newer family, and its power base is in the Talcho region. The original [burgers] of the Talcho region were wiped out near the end of the Migration Wars period when Talcho was sacked and looted by barbarians, who quickly located and executed those of high rank in Talcha society. The Matalin family rose from the ashes and into the vacuum, rebuilding its once-famous city of Matalin into an economic center in the modern Talcho region. The Matalin have historically taken issue primarily with the Manco, due to that family's presence in Talcho as well, the Manco being "local foreigners" of Mancha/Capaca culture. The Matalin have within the past two generations strongly consolidated their hold on Talcho politics and society since the creation of the iron mines to the NE. All iron must go through the city of Matalin and Talcho, and using this extreme leverage, the Matalin have enjoyed a huge lift in their status and power locally, and even now are known throughout the Empire as important players. As Talcho continues to expand and grow in economic and strategic importance, the Matalin are set to see their fortunes grow even more wildly. Talk of construction of a geopolitically important canal through the Pan Isthmus (within Hazco Talcho) may make the Talcho equals to the Huayna some day.

The Matalin family is a newer family, and its power base is in the Talcho region. The original [burgers] of the Talcho region were wiped out near the end of the Migration Wars period when Talcho was sacked and looted by barbarians, who quickly located and executed those of high rank in Talcha society. The Matalin family rose from the ashes and into the vacuum, rebuilding its once-famous city of Matalin into an economic center in the modern Talcho region. The Matalin have historically taken issue primarily with the Manco, due to that family's presence in Talcho as well, the Manco being "local foreigners" of Mancha/Capaca culture. The Matalin have within the past two generations strongly consolidated their hold on Talcho politics and society since the creation of the iron mines to the NE. All iron must go through the city of Matalin and Talcho, and using this extreme leverage, the Matalin have enjoyed a huge lift in their status and power locally, and even now are known throughout the Empire as important players. As Talcho continues to expand and grow in economic and strategic importance, the Matalin are set to see their fortunes grow even more wildly. Talk of construction of a geopolitically important canal through the Pan Isthmus (within Hazco Talcho) may make the Talcho equals to the Huayna some day. The Guacan family is really a somewhat loose assortment of Guacana families who preexisted the Capaca-Mancha invasion of their territory. In return for peaceful coexistence and support in the early generations of Inca settlement in the Dark Territories, the Gaucan were given considerable advantages, with heditary privileges attached, that have allowed them to stay on top of all territory east of the Chupat, including more recent expansions into the Tamazono (where those local families have been mostly oppressed and subjugated by both Guacan and English). Since L'Chulla, their base and home, is fairly remote from the western, coastal part of the Empire, the Gaucan have had relatively little interference from the other, preexisting established families. The Guacan, being a more fractuous and dynamic group, being relatively outside the old power structures of the coast, removed from the centralized capital of the Empire, and having built up a mini-empire based not on resource extraction and food production (save bananas) but rather commerce, have found themselves to be a liberalizing force in the Empire not only in terms of politics but also in terms of trade and business. The Guacan "family", despite being built upon hereditary privilege, has tended to be fairly loose with the rules granted to it by the central government, and has tended towards a more egalitarian and merit-based society within the "Dark" territories.

The Guacan family is really a somewhat loose assortment of Guacana families who preexisted the Capaca-Mancha invasion of their territory. In return for peaceful coexistence and support in the early generations of Inca settlement in the Dark Territories, the Gaucan were given considerable advantages, with heditary privileges attached, that have allowed them to stay on top of all territory east of the Chupat, including more recent expansions into the Tamazono (where those local families have been mostly oppressed and subjugated by both Guacan and English). Since L'Chulla, their base and home, is fairly remote from the western, coastal part of the Empire, the Gaucan have had relatively little interference from the other, preexisting established families. The Guacan, being a more fractuous and dynamic group, being relatively outside the old power structures of the coast, removed from the centralized capital of the Empire, and having built up a mini-empire based not on resource extraction and food production (save bananas) but rather commerce, have found themselves to be a liberalizing force in the Empire not only in terms of politics but also in terms of trade and business. The Guacan "family", despite being built upon hereditary privilege, has tended to be fairly loose with the rules granted to it by the central government, and has tended towards a more egalitarian and merit-based society within the "Dark" territories.

Comment